Over the past few days I’ve been paying attention to the problems that have troubled the launch of healthcare.gov. What I’ve compiled here is an outsider’s perspective and my technical analysis should be treated as educated speculation rather than insider knowledge or anything authoritative. All other commentary here should be treated as my own personal perspective as well. I state these disclaimers because I’ve had no direct involvement with this project and the only information I have to work with is what’s available to the public so some of my claims might be inaccurate. It’s also worth noting that I do know some of the people involved with the project and I’ve worked with some of the companies that were contractors, but I’ve gone about trying to understand this in an independent and unbiased way. Real accountability may be warranted for some of the problems we’ve seen so far, but I’m less interested in placing blame and more interested in simply learning what happened to help ensure it doesn’t happen again.

Context

To be clear, the problems I’m referring to are specifically the issues relating to errors and an unresponsive website when creating a new account for the Federal Facilitated Marketplace hosted on healthcare.gov. The healthcare.gov website is also used to provide related information and to redirect people to State Based Marketplaces hosted by their own states where they exist, but those aren’t the things I’m talking about here.

Unfortunately, many of the more political perspectives around the problems with this website have been illogical and much of the reporting in the news has either appeared to be inaccurate or so vague as to be meaningless. For example, some have claimed that problems with the website indicate that the Affordable Care Act is a bad idea and won’t work, but that’s a radical distortion of logic. This claim is like saying that a problem with an automatic sliding door or a broken cash register at a grocery store indicates that the grocery store (and better access to food) is a bad idea and won’t work. Others have claimed the high demand that caused glitches was unexpected, yet at the same time claim that glitches with the launch of a new product should be expected. Many of the news reports about the problems attempt to provide technical analysis, but mostly fail in identifying anything relevant or specific enough to be accurate or informative.

I do agree that the problems revealed themselves as a result of high demand. Exceeding capacity is a good problem to have, but it’s still a problem and it’s even a problem that gone unchecked could erode the kind of popularity that overwhelmed the system to begin with. I also think this is a problem that can be prevented and should never happen again. It’s true that Americans still have many more months of open enrollment, but first impressions really do matter, especially with something as sensitive as a new health care program.

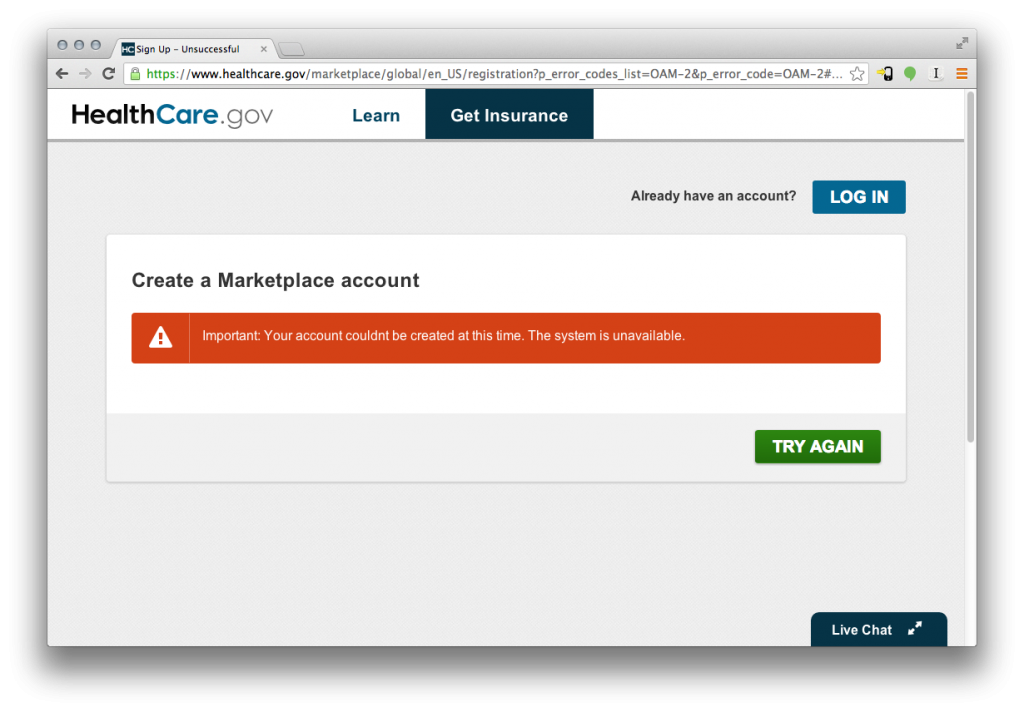

It would be wonderful if an official postmortem was published to help us understand what happened with the launch and prepare us enough to prevent similar situations in the future. As an outsider’s perspective, my analysis shouldn’t be considered anything like that, but it is worth noting that the worst problems with the website are likely already behind us. As Alex Howard reports, there are indications that improvements in the past few days have made an impact, but things still look like they could be going more smoothly. A test conducted by myself today showed that there were basically no wait times whatsoever, but I was still unable to create a new account, receiving the error displayed above instead.

Until problems are fully resolved and until anything resembling a postmortem exists, there will be demand for more answers and better reporting on what has happened. My motivation for writing this is partly that “unexpected demand” or “inevitable glitches” haven’t been satisfying answers, but I’ve also been unsatisfied with the reporting. The best analysis I’ve seen so far has been by Paul Smith (also syndicated on Talking Points Memo) and Tom Lee (also syndicated on the Washington Post Wonkblog). Part of the reason why Paul and Tom’s writing is good is because it actually attempts to distinguish the different components of the healthcare.gov infrastructure and explain the architectural significance of decoupling components in an asynchronous way. Both of these pieces also point out that the frontend of the website, a Jekyll based system, was not the problem despite the many attempts at technical analysis in major publications that have tried to place fault there without looking further. Yet while Paul and Tom definitely seemed to get broad strokes right, I wanted more detail.

After reading Paul’s piece I started a thread among the current and past Presidential Innovation Fellows to see if anyone knew more about what was going on. Basically none of us had direct knowledge of the technical underpinnings of the system, but being furloughed and eager to fix problems turned this into one of the most active discussions I’ve seem among the fellows. I also saw similar discussions arise among the Code for America fellows. Over the course of a day or so we shared our insights and speculation and some reported on their findings. Kin Lane described his concerns about the openness and transparency of the project, especially the conflation of the open source frontend and the blackbox backend. Clay Johnson wrote about how problems with procurement contributed to the situation. I added most of my technical analysis as a comment on Tom Lee’s blog post and I’ve included that here with some edits:

Technical Analysis

For the basic process of creating an account on healthcare.gov there are several potential areas for bottlenecks: 1) Delivering content to the user 2) receiving account creation data from the user 3) actually generating a new user account 4) validating identity and eligibility based on submitted account data.

As Tom and Paul point out, there is almost certainly no issue with point #1. Even though the frontend content is managed through the Ruby based Jekyll app, it’s basically all generated and delivered as static files which are then served by Akamai’s CDN. Even if there are many opportunities to create efficiencies there, it’s unlikely an issue when you’re just dealing with static files on a robust CDN. Placing blame on this smooth running frontend is frustrating not only because it is inaccurate but it also appears to be just about the only part of the system that was done well and done in a very open and innovative way. There’s smart underlying technology, a clean responsive design, a developer friendly API, and an open source project here. This piece was contracted out to a great DC tech firm called Development Seed and it’s been written about a lot before. (Also see Alex Howard’s piece in the Atlantic). Let’s say it again: this is not the problem.

It’s possible there could be a bottleneck in receiving data as writing to a system is almost always more resource intensive than reading data. The system receiving the data seems totally separate from the Ruby Jekyll code even if it appears on the same domain. It appears to be a Java based system as the response headers identify:

X-Powered-By:Servlet 2.5; JBoss-5.0/JBossWeb-2.1 on the account creation form POST to https://www.healthcare.gov/ee-rest/ffe/en_US/MyAccountEIDMUnsecuredIntegration/createLiteEIDMAccount

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Server: Apache

X-Powered-By: Servlet 2.5; JBoss-5.0/JBossWeb-2.1

sysmessages: {"messages":["Business_ee_sap_MyAccountEIDMIntegration_CreateLiteEIDMAccount.OK_200.OK"]}

Content-Length: 181

Content-Type: application/json

X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN;

X-Server: WS01

Expires: Sat, 05 Oct 2013 01:22:59 GMT

Cache-Control: max-age=0, no-cache, no-store

Pragma: no-cache

Date: Sat, 05 Oct 2013 01:22:59 GMT

Connection: keep-alive

Vary: Accept-Encoding

Set-Cookie: JSESSIONID=A965DE6747123123275DCA1A40CBB16.green-app-ap50; Path=/ee-rest; Secure; HttpOnly

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *

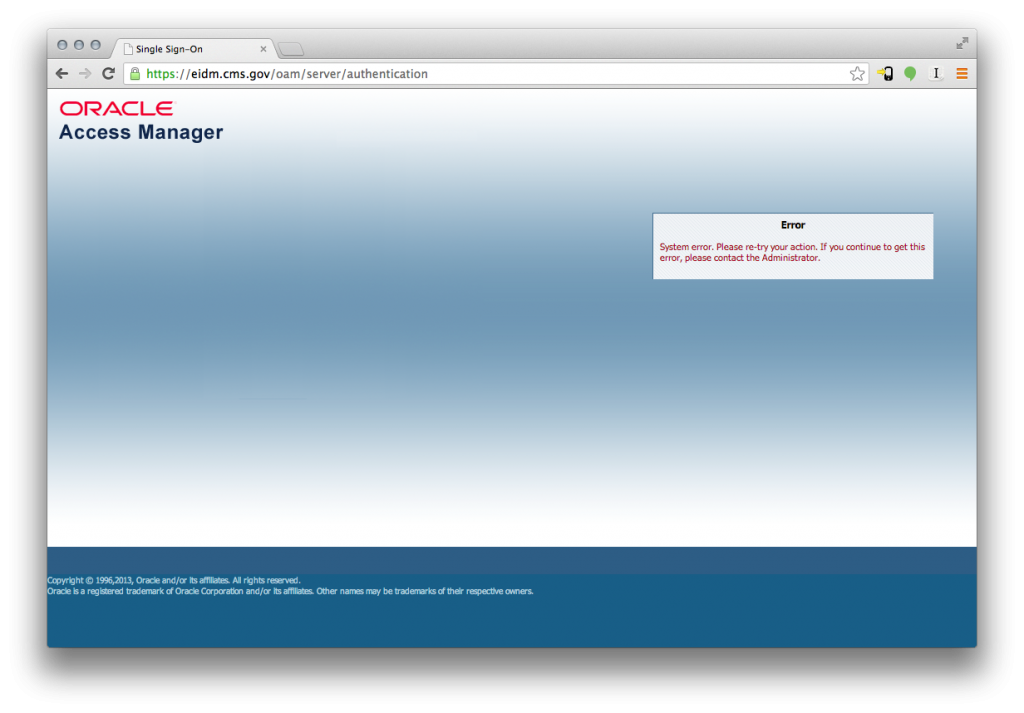

It’s unclear to me if this Java based system is able to do any deferred processing or act as a parallel autonomous system or if it relies on direct integration as a slave to another system. The aforementioned POST URL does refer to another system, the EIDM. The EIDM mentioned here is almost certainly the CMS’s (Center for Medicaid and Medicare) Enterprise Identity Management system. The login form on healthcare.gov also seems to point directly to the EIDM which appears to be an Oracle Access Manager server: https://eidm.cms.gov/oam/server/authentication

You can read more about the EIDM system and its contract on recovery.gov and the IT Dashboard but the best description I’ve seen so far comes from LinkedIn where it appears next to 11 team members associated with the project. Here’s that description:

EIDM is the consolidated Identity and Access Management System in CMS which is one of the largest Oracle 11gR2 Identity and Access Management deployment in the world with integrated all Oracle components to support 100 million users including providing Identity and Access Management Services for Federal Health Insurance Exchange as well as health insurance exchanges in all 50 states that use FFE level of IDM integration, and 100 of CMS federal applications.

Services available from EIDM have been grouped into four main services areas (registration service, authorization service, ID lifecycle management service, and access management service). CMS will make remote electronic services available in a reliable and secure manner to providers of services and suppliers to support their efforts to better manage and coordinate care furnished to beneficiaries and Exchange applicants of CMS programs.

Identify and Access Management services will provide identity and credential services for millions of partners, providers, insurance exchanges enrollees, beneficiaries and other CMS nonorganizational users; and thousands of CMS employees, contractors and other CMS organizational users. EIDM accepts other federal agency credentials provided to CMS from the Federated Cloud Credential Exchange and provides secure access to the CMS Enterprise Portal

It’s unclear to me how that Java backend and the EIDM connect with one another, but together they could account for potential bottlenecks as described by points #2 or #3. My guess is that any identity/eligibility verification (#4) happens totally separately and wouldn’t cause the issues on account creation. Nevertheless, even if that Java backend and the EIDM are totally separate systems there still could be a need to design them in a more decoupled way to allow for better deferred or parallel processing.

As an aside, the reason I pointed out “Java” and “Ruby” is partly superfluous, but refers to people who’ve made references to Twitter’s past performance issues which some have claimed to be relating to Ruby and Java. Twitter was originally written in Ruby and is now mostly driven by Java or other JVM served languages. In the case of the Ruby used for Healthcare.gov, it should be pretty irrelevant because the Ruby is primarily used to generate static files (using Jekyll) which are then served by a CDN.

Transparency

There are a few other things that could also use more clarification: One, worth emphasizing again, is the conflation of the frontend that’s all developer friendly and open source (see https://www.healthcare.gov/developers) and this backend that’s very opaque. As people have attempted to understand the problem, this conflation has been misleading and a cause for confusion. If everything had run smoothly there would be less need to clarify this, but so far the wrong piece of the product and the wrong people have been criticized because of this conflation. This is much of what Kin Lane wrote about. Another issue worth clarifying is the assumption that the federal government has the same access to agile rapidly scalable hosting infrastructure that the private sector has. Unfortunately, the “cloud” hosting services typically used in government pale in comparison to what is readily available in the private sector.

From a hosting infrastructure perspective, these kinds of scalability problems are increasingly less common in the private sector because so much has been done to engineer for high demand and to commoditize those capabilities. When an e-commerce website crashes on Cyber Monday, a whole lot of money is lost. This is why companies like Amazon have invested so much in building robust infrastructure to withstand demand and have even packaged and sold those capabilities for others to use through their Amazon Web Services (AWS) business. One major flaw with comparisons to the private sector is that it is much easier to do phased roll-outs and limited beta-tests for new websites and it is much easier to acquire the latest and greatest infrastructure platforms like AWS, OpenStack, OpenShift, OpenCompute, and Azure. The main reasons for these discrepancies are about ensuring fairness and equitable access, just like many other distinctions between the private and public sector. A phased rollout of healthcare.gov would probably seem unjust because of whomever got early access. Furthermore, many of the procurement policies that make access to services like AWS difficult have been put in place to prevent corrupt or unjust spending of taxpayers’ money. Unfortunately many of these policies have become so complicated that the issues get obfuscated, they repel innovative and cost effective solutions, and ultimately fail to achieve their original intent. Fortunately there are programs like FedRAMP that look like they’re starting to make common services like AWS and Azure more easily available for government projects, but this is far from commonplace at the moment. There’s also a lot more work needed to improve procurement to attract better talent for architecting good solutions. While the need for a more scaleable hosting environment was likely part of the problem here, it was probably more about the design of the software as Paul described. In this project, Development Seed seemed like an exception to the typical kind of work that comes out of federal IT contracts. The need to improve procurement is what Clay wrote about.

Improvements

Aside from the deeper systemic issues that need attention, like procurement and open technology, there are some more immediate opportunities to prevent situations like this: 1) Better testing 2) Better user experience (UX) to handle possible delays 3) Better software architecture with more modularity and asynchronous components.

#1 Better testing: The issues with excessive demand on the website should’ve been detected well before launch with adequate load testing on the servers. The reports I’ve seen suggest that there was load testing or preparations for a certain load, but that the number of simultaneous users it was designed to account for was much smaller than what came to be. It might be helpful to ensure that load testing and QA is always conducted independently of the contractors who built the system. I’m not sure if that happened in this case. Perhaps the way those original estimates were determined should be also re-evaluated, but ultimately the design of the system should have accounted for a wide range of possible loads. There are ways of designing servers and software so that they will perform well at varying loads as long as you can add more hardware resources to meet the demand. With an adequate hosting environment that is easy to do in an immediate and seamless way.

It’s worth noting that the contractor’s description of the EIDM system states that it “is one of the largest Oracle 11gR2 Identity and Access Management deployment in the world with integrated all Oracle components to support 100 million users.” I wouldn’t be surprised if this is the largest deployment in the world. That in itself should have been a red flag signaling it might not have proven itself at this scale and deserved extra stress testing.

Another helpful strategy is to allow for real-world limited beta testing or a phased roll out. Unfortunately there are policies in government that make it very difficult to conduct a limited beta test, but there is also the fairness issue I mentioned earlier. In this case, the fairness issue would actually be more of a false perception or fodder for political spin rather than anything substantial. Doing a phased roll out wouldn’t really be unfair because this isn’t a zero-sum resource, those who get insurance before others don’t make it harder or more expensive for those who come later to access the same insurance. In fact, you could almost argue that the opposite is true. It’s also worth noting that no matter how early you sign up, nobody is getting new health insurance under this program until January 1st. In some ways this actually was a phased roll out because open enrollment lasts all the way through the end of March 2014, but because there wasn’t more clear messaging to prevent a rush on day one, we got a massive rush on day one.

#2 Better UX to handle possible delays: A common way for a tech start-up to throttle new users coming to their recently launched platform is to provide a simple email sign-up form and then to send notifications for when they can actually get a real account. Something similar could’ve been provided as a contingency plan for an overloaded sign-up system on healthcare.gov. Instead, users got an “online waiting room” which they had to actively monitor in order to get access. Anything to better inform users of a possible situation like this and allow them to come back later rather than actively wait would have been a significant improvement to the user experience of the website in this situation

#3 Better software architecture with more modularity and asynchronous components. I think Paul Smith’s piece covered this pretty well, but it’s worth emphasizing. In some ways, there was more decoupling of components in this system than you might find in a typical government IT project with a monolithic stack developed by one contractor. The frontend and the backend were very separate systems, but unfortunately the backend couldn’t keep up with the frontend. To prevent that issue from causing a bottleneck the system could’ve been designed with a simple and robust queuing system to allow for deferred processing with good user experience that clearly stated that the user would receive an email when their new account was ready.

Fortunately there are already people working in government on improvements like this. Among the Presidential Innovation Fellows and many other people in government there are discussions about providing better systems for testing and preparing for the kind of extremely high traffic we’ve seen with healthcare.gov. There are also people working to improve many of the policies that make it difficult to get agile and robust IT infrastructure in government. The American people deserve to know their government is not only working to improve healthcare.gov right now but that there are also many people who are working to learn from it and provide more responsive and graceful government services for the future.

This is the most in-depth and intelligent take I’ve read – thanks, and well done.

I know that this system has to interface, at some point, with the IRS and SSA databases. I’m just guessing, but I would think these are some pretty old systems – they may even be mainframes. Do you think that may play a role in this?

I’ve put down a few of my thoughts on this as well – less from the technical side but more from the project management side. I would love to get your thoughts on them – the link is in the profile I created for this reply. Again, excellent detective work.

Pingback: HealthCare.Gov was originally built in a garage

I think the improvements section is the most valuable part. One of the better write ups on this topic I’ve seen.

Pingback: Open by design: Why the way the new Healthcare.gov was built matters | E Pluribus Unum